By Kai Zen (LNP Founder) – (English version)

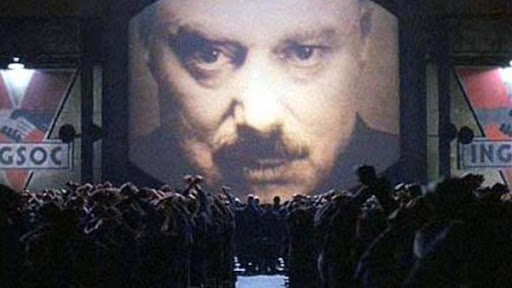

How algorithms, emotions, and hidden interests are reshaping our reality.

Preamble

We live in an era of fractured perceptions. Reality seems to slip through our fingers, replaced by partial and conflicting truths that flare up within increasingly sealed emotional bubbles. We feel observed, our desires anticipated, our fears amplified.

But this is not a random impression.

It is the result of a complex architecture of power – an “invisible geometry” – built at the intersection of algorithmic technology, human psychology, and strategic interests. Understanding this geometry is no longer an intellectual exercise but a necessity to decipher the present and navigate the future. This article aims to map this network, identify its crucial nodes, and unveil the actors pulling the strings.

(SCHEMA / THE GEOMETRIES OF CONTROL: Alias – “Engineering Social Mechanics”)

Let us imagine a structure of interconnected levels:

- Level 1: The Interfaced Individual: Our daily digital life. Devices (smartphones, wearables) act as sensors capturing behavioral data, interpreted by algorithms as “emotions” or “needs.” Personalized interfaces (feeds, recommendations) mediate our experience.

- Cause: Data-driven business models.

- Effect: Micro-conditioning, interface dependency, guided emotional feedback.

- Level 2: The Emotional Macro-cells: Algorithmic aggregation of individuals into homogeneous “bubbles” based on sentiments and worldviews. Internal reinforcement of specific narratives, isolation from divergent perspectives.

- Cause: Algorithmic optimization for engagement (emotional resonance).

- Effect: Extreme polarization, digital tribalism, parallel and irreconcilable realities.

- Level 3: The Nodes of Information Flow: The technology platforms hosting these interactions. They control the algorithms that regulate the visibility, amplification, and suppression of content. They act as gatekeepers of informational and emotional flows.

- Cause: Concentration in the technology market.

- Effect: Immense gatekeeping power, ability to define the agenda and terms of public debate.

- Level 4: The Architects and Beneficiaries (Unicorns & Minotaurs): The actors exploiting this architecture:

- Big Tech (Visible Unicorns): Providers of the infrastructure, holders of the data. Interest: Profit, dominance.

- States (Hidden Minotaurs): Users for surveillance, control, geopolitical influence. Interest: Security, power.

- Political Operatives/Lobbyists (Labyrinth Weavers): Experts in using the system to win elections or promote agendas. Interest: Political/legislative power.

- Concentrated Economic Power (Dragons in the Treasury): Funders and indirect beneficiaries shaping the context. Interest: Profit, regulatory influence.

- Charismatic Leaders (Emotional Catalysts): Figures who ride and amplify the emotional waves generated by the system. Interest: Personal power, base consensus.

(THE ARTICLE)

SECTION 1: THE ALGORITHMIC MIRROR: Stolen Emotions, Invented Needs

We are no longer simple users; we are continuous sources of emotional data. Every like, every pause on a video, every voice search is translated into a psychological profile that algorithms interpret as “needs.”

[Hypothetical Hook 1 – Wellness App Case Study]

(A specific, artificially constructed but plausibly real case study)

“The recent scandal involving the ‘Serenity Now’ app, which promised mental well-being but was found selling aggregated user anxiety data to insurance brokers and targeted advertisers, is emblematic.”

- Cause: The insatiable hunger for data to profile and predict behavior.

- Effect: Our inner lives become commodities, our vulnerabilities access points for commercial and, increasingly, political manipulation. Technology doesn’t respond to our needs; it anticipates, shapes, and sometimes creates them, only to offer a paid solution or a political scapegoat.

- Profound Implication: Loss of emotional authenticity and decision-making autonomy.

Case Study Analysis: “Serenity Now” (Theoretical Scenario)

The theoretical “Serenity Now” case highlights a growing problem in the mental wellness app sector: the monetization of sensitive user data. The app, marketed as a digital sanctuary for managing anxiety and stress, was hypothetically exposed for selling aggregated emotional state data to insurance brokers and advertisers. This theoretically allowed insurance companies to assess psychological risk profiles and advertisers to target vulnerable users with manipulative ads.

This phenomenon is not isolated. Many wellness apps operate in a regulatory gray area, collecting personal data with opaque consent forms or under the vague label of “anonymous data.” However, even aggregated data can potentially be de-anonymized or used to infer sensitive information, violating user privacy. In the “Serenity Now” scenario, investigations hypothetically revealed that the sold data included detailed metrics on the frequency and intensity of anxiety episodes, correlated with geolocation and lifestyle habits.

This fabricated scandal raises crucial questions:

- User Trust: How can users trust apps promising mental support but commercially exploiting their vulnerabilities?

- Regulation: Are GDPR in Europe and similar laws elsewhere sufficient, or are more specific regulations needed for mental health apps?

- Corporate Ethics: Must tech companies adopt stricter ethical codes, or will profit always prevail?

In our reconstructed simulation, “Serenity Now” suspends operations and faces lawsuits in multiple countries. Users are urged to verify app privacy policies and prefer open-source platforms or those certified by independent bodies. The case underscores the importance of conscious technology use and constant vigilance over digital companies’ practices.

SECTION 2: DIGITAL TRIBES: Inside the Bubbles of Absolute Truth

Algorithms, optimized to keep us glued to the screen, group us into “emotional macro-cells.” Here, reality is filtered, our beliefs obsessively confirmed, empathy towards the “other” atrophied.

[Hypothetical Hook 2 – Regional Elections Case Study]

(A specific, artificially reconstructed but plausibly real case study)

“The recent elections in Saxony (a plausible example) saw an explosion of deepfakes and hyper-targeted memes, different for each ‘bubble,’ depicting the same candidate as a savior to his supporters and a monster to opponents. There was no common debate, only parallel wars between irreconcilable realities.”

- Cause: Algorithmic logic of engagement based on emotional resonance and polarization.

- Effect: Intractable social fragmentation, impossibility of constructive dialogue, fertile ground for extremism.

- Parallelism: The same news about the “climate crisis” is presented as an apocalyptic emergency in one bubble and a globalist hoax in another, both with the same emotional intensity.

Case Study Analysis: Saxony Elections (Plausible Scenario)

This information describes a complex and plausible phenomenon related to the impact of digital technologies—particularly deepfakes, hyper-targeted memes, and engagement algorithms—on the recent elections in Saxony and social fragmentation.

Context of the Saxony Elections:

The regional elections in Saxony (and Thuringia) on September 1, 2024, are real events that significantly impacted German politics. Results showed strong gains for the right-wing nationalist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), exceeding 30% support, and the emergence of Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW), a new party with hybrid left-wing and populist positions, securing 12-16% of the vote. These outcomes highlighted political and social polarization, with the federal governing coalition (SPD, Greens, FDP) reduced to minimal percentages (12.7% in Saxony, 10.6% in Thuringia). Studies, like one from the University of Leipzig, confirmed political fragmentation and electoral volatility, especially among youth, revealing growing dissatisfaction with democracy and an attraction to authoritarian solutions, particularly amid economic and social crises.

Deepfakes and Hyper-Targeted Memes in Saxony Elections:

While there is no specific evidence proving an “explosion” of deepfakes or hyper-targeted memes in the 2024 Saxony elections, the described phenomenon is plausible and consistent with global trends documented in other electoral contexts.

- Deepfakes: Generally, deepfakes pose a growing threat to elections, as highlighted by EU reports ahead of the 2024 European elections. The EU Commission urged platforms like Google, TikTok, and Instagram to adopt measures against AI-generated fakes, recognizing their manipulation potential. Concrete examples include deepfake videos of politicians like Giorgia Meloni and Elly Schlein used for financial scams, or a fake video of Ilaria Salis fueling online hate. In Saxony 2024, while no specific deepfakes were reported, the German context is susceptible. AfD, for instance, utilized polarizing narratives on social media, and the presence of viral content amplifying extreme emotions is documented. A recent case in Romania (2024 presidential elections) showed TikTok manipulated with bots and influencers to promote a pro-Russian candidate, demonstrating similar techniques are already in use in Europe. Assessment: The absence of direct evidence for Saxony doesn’t preclude the possibility of deepfakes, given their low production cost and difficulty in tracking. The description of a candidate depicted as a “savior” to supporters and a “monster” to opponents reflects real digital propaganda tactics, like those used by Salvini’s “The Beast” in Italy, aimed at polarizing through emotional content.

- Hyper-Targeted Memes and Algorithmic Bubbles: Generally, social network algorithms, designed to maximize engagement, favor divisive and polarizing content, locking users into “filter bubbles” or “echo chambers.” This is confirmed by studies like the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025, identifying disinformation as the top global risk, amplifying social and political divides. In Italy, analysis of the 2016 constitutional referendum showed users tend to stay in information environments reinforcing their beliefs, limiting exposure to different viewpoints. In Saxony 2024, polarization is evident, with AfD capitalizing on discontent regarding immigration and the economy, while the Greens attracted youth on climate issues. Memes, often ironic or sensationalist, are common tools for mobilizing voters, as seen in other European campaigns (e.g., Salvini’s post on bottle caps criticizing the Green Deal). The description of “parallel wars between irreconcilable realities” is consistent with the fragmentation of public debate, where each group consumes narratives tailored by algorithms. Assessment: The presence of hyper-targeted memes is highly probable, though not specifically documented for Saxony. The “algorithmic logic of engagement based on emotional resonance” is a well-established reality, as explained by experts like Callum Hood of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, who note that divisive content gains more visibility.

Effects: Social Fragmentation and Extremism:

The described social fragmentation is a real phenomenon, aggravated by social media algorithms. The Global Risks Report 2025 highlights how polarization and disinformation are eroding social cohesion, creating fertile ground for extremism. In Saxony, the rise of AfD and youth electoral volatility reflect a divided society where crisis rhetoric (economic, migratory, climate) fuels authoritarian solutions. The impossibility of a “common debate” is confirmed by studies describing polarization as a barrier to independent opinion formation. Assessment: The described effect is supported by evidence. Social fragmentation in Saxony, combined with the success of extreme parties, demonstrates how digital dynamics can amplify pre-existing divisions, making constructive dialogue increasingly difficult.

Parallelism with the Climate Crisis:

The parallelism drawn is pertinent. The climate crisis is a polarizing issue, with opposing narratives coexisting in different information bubbles. An Advance Democracy report highlighted rising climate disinformation on social media, with content denying climate change or painting it as a “globalist hoax” spread with the same emotional intensity as content presenting it as an apocalyptic emergency. For example, Fridays For Future noted how posts denying climate change can carry the same weight as evidence-based scientific posts due to algorithms rewarding emotionality. In Saxony 2024, while no specific data links the climate crisis to the elections, the theme is globally relevant. The Global Risks Report 2025 identifies extreme weather events and biodiversity loss as top long-term risks, but political polarization hinders coordinated responses. In Germany, the climate crisis has been used by both the Greens to mobilize youth and AfD to fuel anti-establishment narratives, such as opposition to the Green Deal. Assessment: The parallelism is realistic and well-documented. The climate crisis, like other complex issues, is fragmented into opposing narratives reinforced within respective bubbles, amplifying polarization and hindering shared consensus.

Conclusion on Case Study Plausibility:

The information provided is plausible but not fully verified for the 2024 Saxony elections. There is no direct evidence of an “explosion” of deepfakes or hyper-targeted memes specific to this context, but the described phenomenon aligns with global trends documented in other electoral processes (e.g., 2024 European elections, US presidential elections, Romania). Polarization, social fragmentation, and the impact of engagement algorithms are established realities, supported by sources like the Global Risks Report 2025 and academic studies. The parallelism with the climate crisis is accurate and reflects real dynamics of disinformation and information bubbles.

SECTION 3: THE SLUICE GATE MASTERS: Who Decides What We See (and Feel)

Power lies not only in content but in controlling the flow. Big Tech (Meta, Google, TikTok, X, etc.) are the “sluice gate masters” of information. They decide, through opaque algorithms, what emerges and what disappears.

[Real Hook 3 – EU AI Regulation]

The heated debate in Brussels over new regulations for AI in election campaigns highlights precisely this node. Platforms declare neutrality, but their architecture is political. The slowness in removing coordinated disinformation during the Saxony elections (Hook 2) was not a bug, but a feature of a system optimized for virality, not truth.

- Cause: Technological oligopoly and attention-based business models.

- Effect: De facto control over public opinion, systemic vulnerability to coordinated manipulation (state or private).

- Vertical Analysis: An algorithmic decision in Palo Alto can determine the outcome of a local election in Molise.

SECTION 4: UNICORNS AND MINOTAURS: Identifying the Powers in the Network

Who, then, are the actors benefiting from and maneuvering this geometry?

- Big Tech (Ambivalent Unicorns): They provide the arena and the rules of the game, profiting from the activity within, whatever it may be. Their neutrality is a convenient fiction.

- States (Silent Minotaurs): They use the network to surveil citizens and conduct increasingly sophisticated influence operations, often invisibly. The “hybrid war” is fought here.

- Political Strategists (Adept Weavers): They have learned to use algorithms to microtarget voters with emotionally charged messages, bypassing rational debate.

- Global Capital (Hidden Dragons): [Hypothetical Hook 4 – Sovereign Fund] “The scandal of the ‘Oasis Fund’ sovereign wealth fund, which secretly financed social media campaigns denying climate change in Africa to protect fossil fuel investments, shows how powerful economic interests actively shape perceived reality, using the same platforms and techniques.”

- Populist Leaders (Emotional Prophets): They are the public faces capitalizing on the fears and hopes amplified by the system, offering simple solutions and clear enemies.

[Hypothetical Hook 4 – Sovereign Fund Case Study Analysis]

(A case study set in a hypothetically real environment)

Context: This case study concerns a hypothetical scandal involving the “Oasis Fund” sovereign wealth fund, accused of secretly financing climate denial social media campaigns in Africa to protect fossil fuel investments, thereby manipulating reality perception via digital platforms.

The “Oasis Fund”: There is no documented evidence of a sovereign wealth fund named exactly “Oasis Fund” involved in such a specific scandal. However, an entity named Oasis Africa VC Fund exists, a $50.5 million private equity fund investing in SMEs in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, focusing on sectors like education and healthcare, unrelated to climate denial or fossil fuels. The hypothetical “Oasis Fund” likely serves as a fictional placeholder representing the real phenomenon of sovereign or investment funds financing fossil fuel activities. Real funds like Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global or Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund have historically invested in fossil sectors, though recent direct involvement in denial campaigns in Africa isn’t documented.

Climate Denial Campaigns in Africa: The phenomenon of social media climate denial campaigns in Africa, funded to protect economic interests, is real, though not specifically linked to an “Oasis Fund.” A key example involves Jusper Machogu, a Kenyan farmer promoting climate denial and fossil fuels in Africa via social media (primarily X). He received over $9,000 in donations, some linked to Western fossil fuel industry figures and denial groups. BBC Verify found most of his followers are in the US, UK, and Canada, suggesting international network amplification. Machogu denies external influence, but the case shows how external interests can use local influencers to promote pro-fossil narratives. Investigative journalist Amy Westervelt noted Africa is seen as a key market for new fossil projects, and such campaigns can build local consent by framing fossil fuels as necessary for development while denying anthropogenic climate change. This aligns the hypothetical “Oasis Fund” case with real dynamics.

Covert Funding and Climate Disinformation: The description of a fund “secretly financing” denial campaigns reflects well-documented tactics of the fossil fuel industry. Over decades, majors like ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, and BP have spent millions on climate disinformation, funding think tanks and front groups to sow doubt about climate science (e.g., InfluenceMap’s 2019 report on $1B+ spending post-Paris Agreement; funding of Cato Institute, Heritage Foundation by Koch brothers; Exxon’s Global Climate Coalition spreading disinformation despite internal science acknowledging risks). Africa’s lower climate literacy makes it vulnerable, potentially slowing climate action in favor of short-term economic gains from fossil projects.

Protecting Fossil Fuel Investments: The motive of protecting fossil investments is plausible given Africa’s economic context. Significant oil and gas extraction projects attract investment (Nigeria, Angola, Mozambique, Uganda). However, the global shift to renewables creates risks of “asset stranding.” Denial campaigns can maintain public/political support for these projects, countering climate urgency narratives. A real example is Japan funding a coal plant in Bangladesh as “climate finance,” despite criticism. The “fossil fuels for development” narrative is often promoted in Africa to justify new projects.

Use of Digital Platforms and Reality Fragmentation: The description of the “Oasis Fund” using “the same platforms and techniques” to shape perceived reality accurately reflects social media algorithm functions. Platforms like X, Facebook, and TikTok amplify emotional, polarizing content, creating information bubbles. The Center for Countering Digital Hate found 69% of Facebook climate denial content comes from just 10 publishers, showing disproportionate impact. In Africa, influencers like Machogu leverage these dynamics, often amplified by Western networks. Reality fragmentation (climate crisis as emergency vs. hoax) applies here, potentially undermining climate adaptation efforts.

Assessment of Hypothetical Scandal: While there’s no evidence of a specific “Oasis Fund” scandal, the described scenario is highly plausible and mirrors real, documented dynamics. The fossil fuel industry has a history of covertly funding climate disinformation using digital platforms to protect economic interests, particularly targeting vulnerable regions like Africa. Cases like Jusper Machogu confirm the plausibility. “Oasis Fund” is fictional, but the problem it illustrates is real and current.

Parallelism: While the State acts with security and control logic, capital acts for profit and regulatory influence, and political strategists for electoral victory. All converge on using the same tools: the algorithms of the platforms, which become both the battlefield and the primary weapon.

SECTION 5: THE UNVEILED DESIGN: The Systemic Network of Emotional Control

This is not a single conspiracy, but an emergent system where diverse interests converge in exploiting technology to manipulate perception and behavior on a mass scale. Causes (business models, pursuit of power) generate effects (polarization, disinformation, erosion of democracy) that feed back into the system.

It’s a complex geometry where each level influences the others: platform decisions (Level 3) enable actors (Level 4) to shape bubbles (Level 2), conditioning the individual (Level 1), whose data feeds back into the system.

(CONCLUSION: THE INCANDESCENT SPINDLE)

Where do all these threads intertwine? In the “incandescent spindle” where three elements converge: Data (the raw material extracted from our lives), Algorithms (the engines processing data and regulating flows), and Interest (the driving force, be it economic profit, political power, or strategic control).

This Data-Algorithm-Interest nexus is the pulsating heart of the invisible geometry of contemporary power. It is an engine that not only reflects reality but actively produces it, shaping our emotions, guiding our choices, and defining the boundaries of the possible. Blowing the dust off this design is not just an act of understanding, but the first, indispensable step towards imagining and building alternatives founded on transparency, autonomy, and a renewed shared humanity, before the labyrinth closes definitively behind us.

Scopri di più da NRG News: Il Futuro a portata di Click

Abbonati per ricevere gli ultimi articoli inviati alla tua e-mail.